For more than a decade, the federal government has announced at least one healthcare fraud takedown each year. And on September 30, 2020, the federal government announced what it called the “largest” such action. But this claim is based on some questionable methodology that I think would surprise reporters, including changing what the government counts as a “takedown” and counting many cases that had been previously announced.

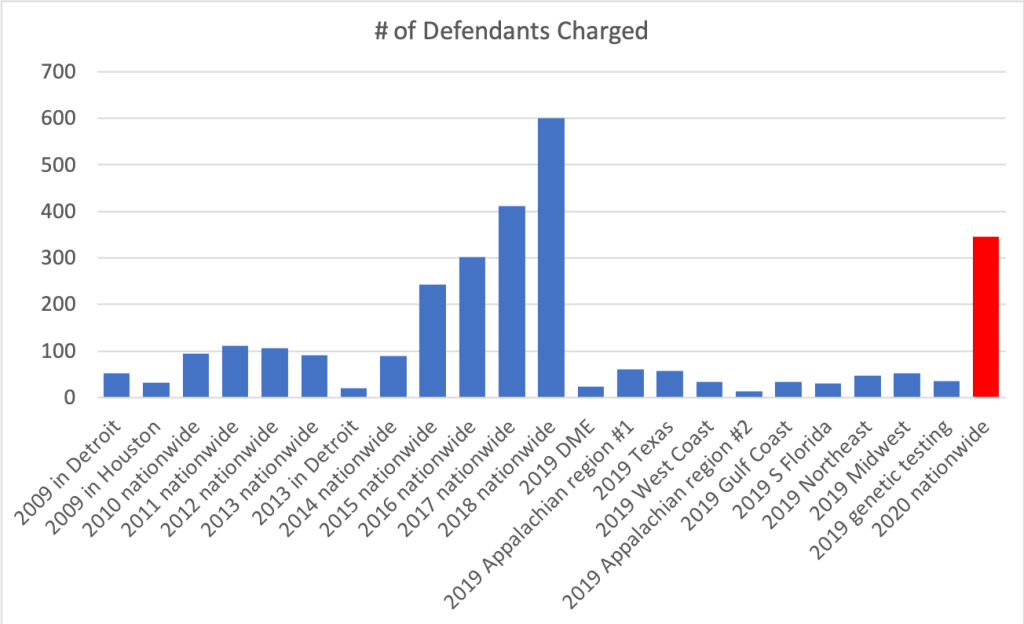

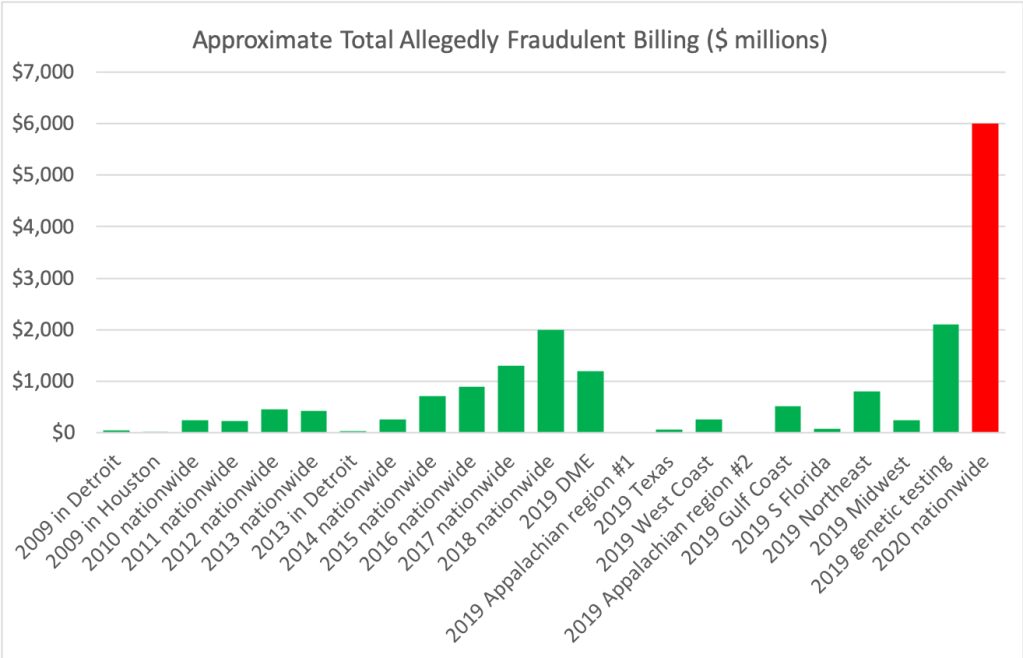

In prior takedowns, the government measured the size of a takedown by the number of defendants charged and the amount of allegedly fraudulent billing.

By number of defendants, this takedown fell far short of the 2018 takedown, which involved almost twice as many defendants as the 2020 takedown.

By amount of allegedly fraudulent billing, the 2020 takedown is indeed the largest, but the government apparently got there by applying a new way of counting that is shaky and potentially misleading.

Based on my review of the cases counted by the government as part of the 2020 takedown, many of the cases were NOT charged on or around the date of the “takedown,” in contrast to prior takedowns. Instead, about half the cases actually were charged more than a month earlier, some many months earlier. And about 25 percent of the cases had already been announced by the Department of Justice, and a few had even been announced as part of last year’s takedowns.

Unfortunately, this raises concerns about the credibility of the government, or at least some parts of the government. I was an Assistant United States Attorney in Chicago for 11 years and was senior counsel to my office’s healthcare fraud unit from 2017 through early 2019, and I did not see anything like this in my time (I want to point out that my old office’s numbers look fine, and I have no problem with how its cases were counted as part of the takedown).

Here’s some context.

The federal government began doing healthcare fraud (“HCF”) takedowns around 2009, and the first HCF takedowns were definitely “takedowns” in the sense of coordinated law-enforcement actions that occurred simultaneously to stop ongoing criminal conduct. In June 2009, agents conducted an “early morning takedown” resulting in multiple arrests that day in a few cities. A month later, agents conducted a similar “early morning takedown” resulting in arrests that day. and

HCF takedowns became national from 2010 through 2018. Most years, the number of people who were charged increased, and the total amount of claimed losses increased. The takedowns also shifted away from arrests that occurred that day to cases that were charged on or shortly before the takedown. I’m okay with this, even if it arguably is stretching the definition of “takedown.” In those years, takedowns counted the following: arrests, searches, new charges, and the announcement of recent charges.

In 2019, the government shifted its press strategy. Instead of announcing one HCF takedown for the entire year, the government announced multiple HCF takedowns focused on a particular healthcare sector or geographic region. One (Brace Yourself) focused on durable medical equipment, another focused on genetic testing, and others focused on Texas, the West Coast, the Appalachian region (two takedowns), the Gulf Coast, South Florida, the Northeast, and the Midwest.

The DME takedown in April 2019 was a classic “takedown,” involving coordinated arrests based on sealed indictments, the execution of 80 search warrants, and administrative actions against multiple companies. And I think that this was a great strategic move for the government – it spotlighted a major problem that I have written about elsewhere and has had significant impact even beyond the specific people who were arrested.

But I noticed something odd about at least one of the regional takedowns in the fall of 2019.

In the Texas press release, the Department of Justice announced enforcement actions, charges, and arrests that occurred “today.”

But the government had already charged many of the people mentioned in the press release much earlier.

Of the 21 people who were specifically cited as being charged in the Northern District of Texas, 10 had actually been charged much earlier and had even been the subject of prior DOJ press releases.

- Seven people had been charged in March 2017, when a press release was issued. One of the defendants pled guilty in July 2019. The government then re-charged the six remaining defendants and added a seventh in September 2019.

- One had been charged in 2018, when a press release was issued. This defendant had been arrested in June 2018 and apparently had considered pleading guilty. The government then re-charged the defendant in September 2019.

- And two more had been charged in the DME takedown months earlier. The government then brought new charges against the defendants in September 2019.

This struck me as odd and potentially troubling. Yes, there technically had been some government actions in September 2019 as slightly new charges were brought against each of these defendants, but these normally would not have been significant or worthy of a press release. Moreover, the press release made it sound like these people had been arrested “today,” rather than re-charged slightly in the past few weeks.

In 2020, the government went back to announcing one national takedown, which it did on September 30. The government referred to “today’s enforcement actions” and “the cases announced today,” and claimed that this was the “largest health care fraud and opioid enforcement action in Department of Justice history.”

But let’s take a closer look at the “takedown.”

First, in terms of the number of defendants, the 2020 takedown falls far short of prior takedowns. There were 345 defendants announced in the 2020 takedown, just over half the number announced in the 2018 takedown two years earlier.

Second, the 2020 takedown is the largest in terms of the billings that the government has claimed were allegedly affected by the cases in the takedown ($6 billion).

But, as mentioned above, the government counted a lot of older cases for the takedown and appears to have re-defined what a “takedown” is.

In the takedowns from 2015 through 2018, the vast majority of cases were charged around the time of the takedown. About 85 percent or more of the cases that were designated as part of the takedowns were charged in the month prior to the takedown announcement.

But in 2020, only about half of the cases that were officially designated as part of the takedowns had been charged in the month prior to the takedown announcement.

The 2020 “takedown” was not a coordinated series of arrests that occurred on or about the same day. It was not even a collection of cases that at least occurred shortly before the announcement. Instead, it was more of a conglomeration of cases over the course of the past year, most of which had nothing to do with the others.

If you take out the older cases so that you can compare apples to apples, the 2020 takedown still shows some impressive work by prosecutors and agents, particularly in light of the challenges of investigating crimes during Covid, but it probably is not “historic” and may not be the “largest.”

(If you want to check my numbers, the government has made available indictments and other charging documents for many of the cases in the 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2020 takedowns. Most indictments clearly show when the charges were filed, and I’ve cataloged them by when they were charged in relation to the respective takedown.)

Third, the government counted several older cases that had already been announced and covered in press releases. On top of arrests, searches, new charges, and new announcements of recent charges, the government apparently now counts “re-announcements” as a law-enforcement action.

- For example, the government included three cases from Florida which had been charged and announced in 2019: one (McNeal) had been announced in April 2019 as part of the Brace Yourself takedown, and two (Kahn and Karlick) had been announced in September 2019 as part of that year’s South Florida takedown.

- The government counted several Covid-related cases which had been the subject of press releases in May and June in Georgia, Arizona and California.

- The government included multiple cases relating to Indivior Solutions, which pled guilty in July 2020 relating to the marketing of the opioid-addiction-treatment drug Suboxone back in 2012.

- And, like in Texas in 2019, the government again counted slightly modified charges against people who were charged much earlier and had already been the subject of press releases: a couple who had been involved in a compounding scheme that allegedly ended in 2015 and whose charges were announced in 2018, and a nurse who had been charged for aiding a doctor in committing fraud from 2015 through 2017 and whose charges were announced in 2019.

I was a prosecutor for 11 years and I was a reporter before that, and I believe that coordinated government actions and press releases can be effective tools to stop and deter crime. But I also believe in accuracy and I think it is misleading to claim that unrelated cases that were previously charged and that were previously announced are part of a later “takedown.”

Why does this matter?

First, public companies and their officers commit securities fraud when they manipulate their numbers to make their quarterly or annual results look better than they actually were. The government should not be engaging in similar conduct.

Don’t call it a takedown when it’s not really a takedown. Call it a review or update of cases that have been charged in the past year. This probably will get fewer headlines, but at least it will be accurate.

Second, re-announcements could violate DOJ rules and affect pending cases. Re-announcing a case for a second time just to pump up the numbers for a subsequent takedown causes confusion and could prejudice defendants who were previously charged. Defense lawyers should consider filing motions if the government has re-announced their clients’ cases while the cases were pending, and defense lawyers should consider asking judges to order the government to not do this with their cases.

Third, reporters should review the DOJ’s announcements more carefully going forward. The next time the government announces a “takedown,” make sure that it actually is what the public would consider a takedown before calling it such. If the announcement is simply a list of cases that were charged in the past six months or a year, call it that, especially if the cases involved criminal conduct that ended years earlier.

Takedowns can and should continue to be effective tools for law enforcement, but I hope the government is more careful about what it counts and says in the future.

Here is some additional information for disclosure and methodology. When I was in the government, I charged cases that were part of the 2012, 2014, and 2018 takedowns – all my cases were charged on or shortly before those takedown announcements. I noticed the DOJ’s use of old charges while looking at the 2020 takedown, and then decided to check all of the charging documents that the DOJ made available for the cases in the 2020 takedown and to compare the results to the annual takedowns in 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018. I then ran Internet searches to find press releases that had been previously issued for many of the cases in the 2020 takedown. This did not take long once I knew what to look for. Please contact me at slee@beneschlaw.com if you’d like to see my work.

Stephen Lee was an Assistant United States Attorney in Chicago from 2008 through 2019 and served as senior counsel to the healthcare fraud unit in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois. He is now in private practice in Chicago. In his first year in private practice, he was counsel to a doctor in a seven-week Medicare Strike Force trial in the Southern District of Texas, in which he helped win the acquittal and dismissal of multiple charges, including all charges against three co-defendants.