On September 30, the federal government announced its annual healthcare fraud takedown, which involved 345 charged defendants and a lot of work by prosecutors and agents.

I wanted to offer some perspective on the takedown, based on my own time as a former federal prosecutor who handled many healthcare fraud cases and as an attorney who now is in private practice.

Today, I want to start by discussing the largest part of the takedown, which is a continuation of the government’s investigation of fraud involving durable medical equipment, “Operation Brace Yourself.” This investigation was publicly announced in April 2019 and has continued into 2020, when the government announced more DME fraud charges.

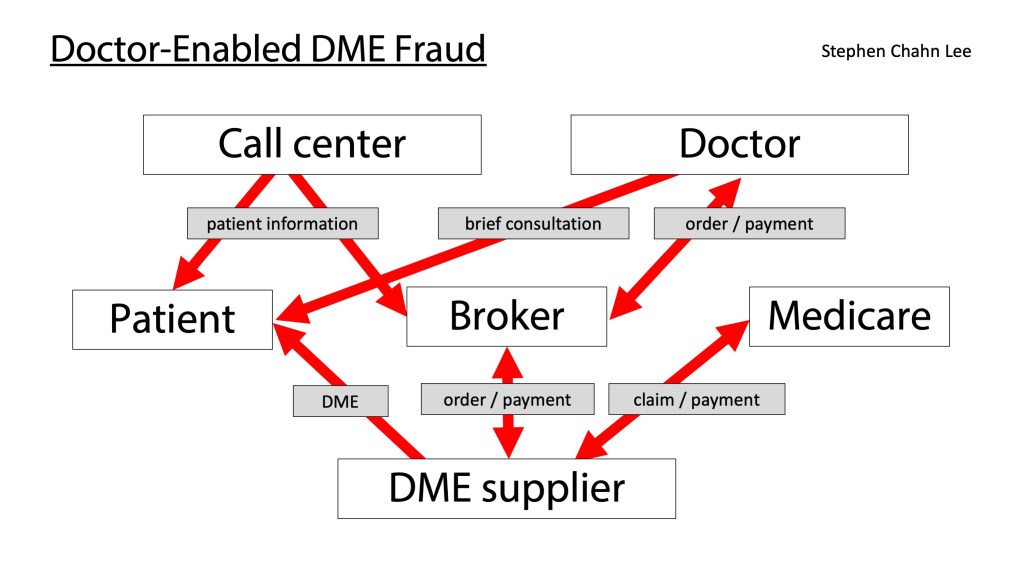

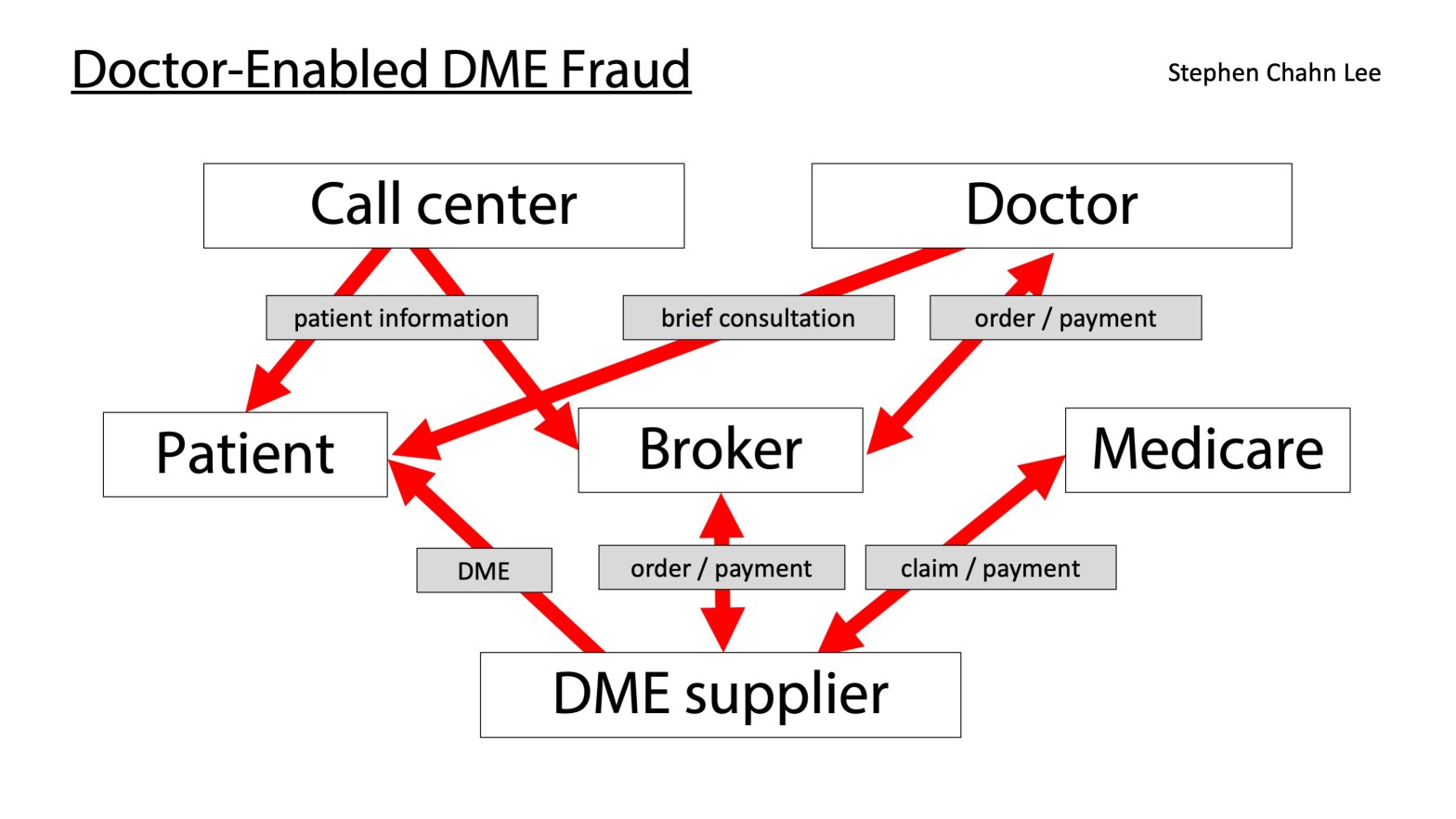

Overall, the kind of fraud that the government has targeted with “Operation Brace Yourself” is a type of fraud that I prosecuted and spoke about when I was a federal prosecutor, what I call “doctor-enabled” healthcare fraud. On Medicare’s behalf, I explained how “doctor-enabled” healthcare fraud worked in a different context (home health) in a Special Medicare Open Door Forum in January 2017, and the same patterns are at work in Operation Brace Yourself and similar government investigations.

In “doctor-enabled” healthcare fraud, doctors are not driving the fraud and they often are not making much money from the fraud. Instead, someone who is not a medical professional uses (a) doctors to enable the billing of claims that benefit the non-medical professional, (b) marketers to solicit patients, often via misleading tactics and payments that violate the Anti-Kickback Statute, and (c) brokers who help arrange everything.

The complicated diagram below summarizes the overall system described in many of the cases in the 2020 takedown. If it helps, I walk through this diagram in a video that you can access by clicking here or on the diagram.

To understand how the fraud works, let me first explain how DME typically is ordered for Medicare patients. The patient sees his or her doctor about a medical problem, and the doctor recommends DME as part of the treatment. The doctor then sends an order to a DME supplier. The DME supplier sends the DME to the patient, bills Medicare for the DME, and is paid by Medicare. The doctor continues to treat the patient and sees how the DME works.

In “doctor-enabled fraud,” things work very differently. Instead of a doctor driving the process, the process is driven by a non-medical professional, typically a broker who works with and for DME suppliers.

- Step one. The non-medical professional uses marketers to find patients and pays the marketers, often on a per-patient basis that can violate the federal Anti-Kickback Statute.

- Step two. Many of these patients already have primary-care physicians who probably would not be receptive to getting asked by a marketer to order braces for their patients. Patient brokers then go around the patient’s primary-care physician by using doctors who have no prior relationship with the patient and who have some financial incentive to order the services or items that would benefit the non-medical professional. Often, the doctors who “enable” the fraud are getting paid very little compared to other people. In many of the cases that are part of the 2020 takedown, doctors were getting paid just $20 to 40 per consultation or order, a relatively small amount given how much those orders cost Medicare.

- Step three. The broker sells or provides the order to a DME supplier. The DME supplier then sends the DME to the patient, bills Medicare, and gets paid by Medicare. But as a result of this system, patients often get DME that is not actually needed or helpful, and Medicare pays for large amounts of unnecessary DME.

This overall system has cost Medicare billions of dollars and explains one thing that you might find odd about the government takedowns. In each of the takedowns from 2014 through 2020, the vast majority of people who are charged with healthcare fraud crimes are NOT medical professionals, but businesspeople or marketers or other non-medical professionals. Medical professionals have made up less than 30 percent of the people charged in each of the takedowns for which the government has supplied this information.

This system also explains some of the red flags that I have observed in publicly available Medicare data.

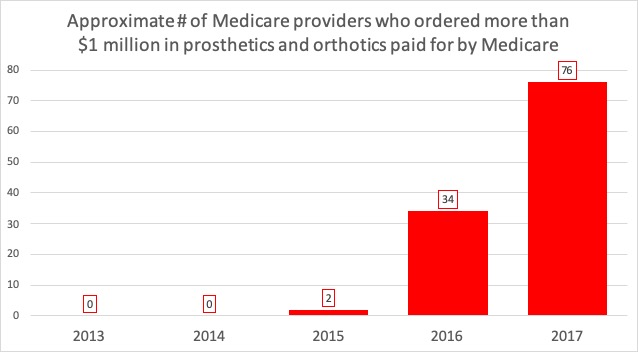

Consider this. In 2013 and 2014, according to publicly available data, there were no Medicare providers anywhere in the country who ordered more than $1 million in prosthetics and orthotics that were paid for by Medicare. Similarly, there were no Medicare providers anywhere in the country who ordered prosthetics and orthotics for more than 1,000 Medicare patients.

That changed.

| Approximate # of Medicare providers who ordered more than $1 million in prosthetics and orthotics paid for by Medicare | Approximate # of Medicare providers who ordered prosthetics and orthotics for more than 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries | |

| 2013 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 2 | 1 |

| 2016 | 34 | 22 |

| 2017 | 76 | 57 |

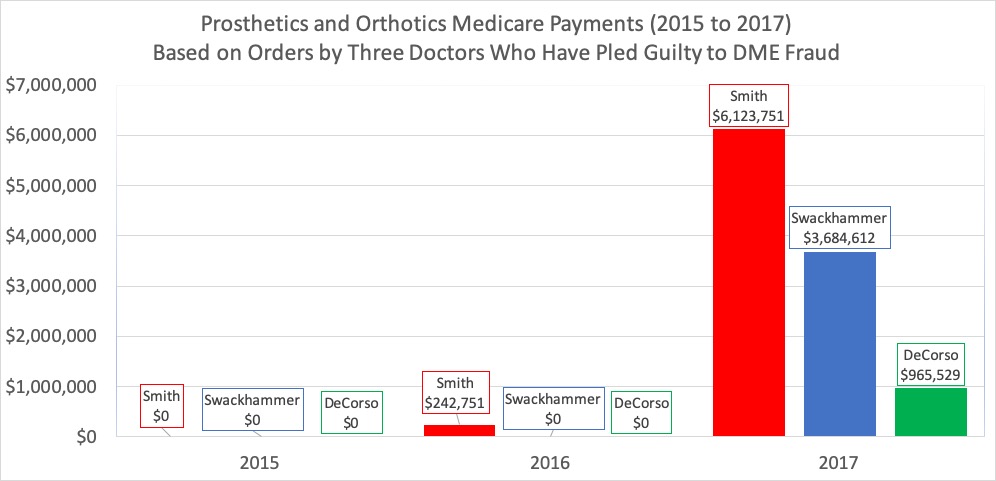

By 2017, there was a large number of Medicare providers who were ordering huge amounts of prosthetics and orthotics, including several doctors who have been charged in the 2019 and 2020 takedowns and who have already pled guilty (the number probably grew in 2018 and early 2019, but data is not yet publicly available). The graph below shows how the payments associated with three doctors (Alleyne Smith, Randy Swackhammer, and Joseph DeCorso) grew suddenly in 2017.

None of these doctors ordered any prosthetics or orthotics in 2015, according to Medicare data.

But by 2017, each was in the top 100 of Medicare providers around the country in terms of Medicare payments for prosthetics or orthotics. Based on my review of the data, each ordered more than $1,000 of prosthetics or orthotics for large numbers of patients. DeCoroso ordered an average of approximately $1,200 in prosthetics or orthotics for more than 800 Medicare patients, and Smith ordered an average of approximately $1,500 in prosthetics or orthotics for more than 3,900 Medicare patients.

What changed? When DeCorso pled guilty in 2019, he admitted that he worked for two telemedicine companies for which he wrote medically unnecessary orders for orthotic braces. He admitted that he wrote brace orders without speaking to the patients and that he concealed the fraud with falsified orders stating that he had “discussions” or “conversations” with patients when he had not actually done so.

While doctors like Smith, Swackhammer and DeCorso have pled guilty to DME fraud, these cases sometimes can be challenging for the government. Generally speaking, the government cannot convict someone of healthcare fraud unless the government can prove that the person knew that what they were doing was illegal. That can be difficult when the doctors have little knowledge of the overall system and are receiving relatively small payments. If a doctor really was naïve or careless or gullible, then the doctor would not have the “willfulness” necessary to be convicted of healthcare fraud.

Doctors involved with DME or other high-risk areas can alert themselves to potential “doctor-enabled” healthcare fraud by asking themselves a few questions.

- Do you know where your patients came from? Are they actually reaching out for help, or have they simply been solicited by marketers?

- Are you actually treating the patient, or are you just ordering one or more particular items or services that you would not order in my typical practice?

- If you are given forms or EMR to fill out, is everything there actually true before you sign?

I hope you enjoyed this perspective. I’ll be covering other aspects of the takedown and healthcare fraud in future posts, including how and why doctors should look at their own data to understand how they may be viewed by the government.

Stephen Lee was an Assistant United States Attorney in Chicago from 2008 through 2019 and served as senior counsel to the healthcare fraud unit in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois. He is now in private practice in Chicago. In his first year in private practice, he was counsel to a doctor in a seven-week Medicare Strike Force trial in the Southern District of Texas, in which he helped win the acquittal and dismissal of multiple charges, including all charges against three co-defendants.

Great idea starting this blog-

LikeLike